He is first a scientist who has mastered as much as man knows about the life process through the ages measured by geology. In dealing with this hazardous subject, Eiseley neither avoids the big questions nor offers glib reassurance for the apprehensive.

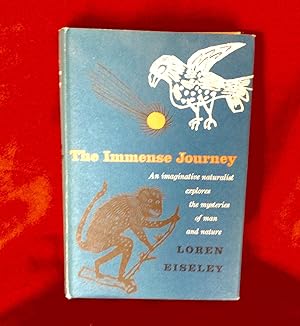

It also brought him the coveted John Burroughs Medal, which goes to a popular book on natural science blending accuracy, originality and good writing.Ī man who spends his life handling the bones, and fossils of his ancestors is bound to reflect on the ultimate significance of life. In 1961 The Firmament of Time earned for him the Pierre Lecomte du Nouy American Foundation Award for the best book tending to reconcile science and religion. For Darwin's Century, a lucidly panoramic account of the development of the concept of evolution, he won the first Phi Beta Kappa Science Prize for 1959's best book on science. When The Immense Journey was published in 1957, it was praised as being "beautifully written" and "a delightful journey, full of beautiful images and fascinating ideas." One reviewer felt "like going out into the street and buttonholing passers-by into sharing his pleasure."Įiseley's two other books earned him the same kind of considered applause. Yet the experts find Eiseley's guidance impeccably accurate, while the common reader receives from him a rare insight into the long and wondrous tale of the evolution of life.Įiseley is a modest man who has responded with a thoughtful humility to the honors that have been showered upon his books. Obviously such an interrelationship is difficult to sustain for either the scientist or the writer. But The Immense Journey involves not only anthropology but also archeology, paleontology, biology, geology and chemistry. Anthropology may be broadly defined as the study of man and his works, past and present. The Immense Journey is a striking instance of his rare talent. What Eiseley has done in scores of articles and three books is to make the ideas and findings of his special fields not only radiantly comprehensible but almost spiritually meaningful to readers whose knowledge of science is slight. Yet many of his peers have accomplished as much and left the plain reader no wiser. As a distinguished anthropologist he has a full measure of academic rewards for genuine accomplishment. Loren Corey Eiseley labors under no such limitation. The fences of the imagination are buckling under the pressure brought against them by the facts and theories of modern science, but few scientists have the writer's imagination that is needed to describe the deepest meaning of their seeming miracles.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)